Making Memes Secure Again

TL;DR

We fuzzed giflib and found two bugs, one of which could be used for a remote DoS and has been assigned CVE 2019-15133. We tried to enhance our setup with structure-aware fuzzing, but this did not outperform standard coverage fuzzing.

Intro

Giflib is a library for processing gif (graphics interchange format) files. Gif files (gifs for short) have a widespread usage, most prominently the preferred file format for short looping videos. Since giflib is used to render Gifs on the client side (most often smartphones), they are an interesting fuzzing target. Can malformed gifs crash giflib or worse? This is the primary question we focused on.

Our approach was to write a simple fuzzing harness that decodes arbitrary gifs. This already yielded pretty good results, in particular an integer overflow, an out of memory and a divide by zero vulnerability. After we submitted the harness to oss-fuzz, we wanted to further extend and came up with the idea of enhancing our coverage guided fuzzing setup with structure aware fuzzing. For that, we specified a protobuf definition of gifs: The fuzzer then takes this definition and converts it into a gif file. Unfortunately, this did not discover further bugs - most likely, because the gif format is simple enough for standard coverage guided fuzzers.

Related work

We are not the first by any means to fuzz test gif parsers. Back in 2014, Michel Zalewski fuzzed and found a potential use-of-uninitialized value issue (tagged CVE-2014-1564 1) in the gif parser bundled with the Firefox browser at the time. Two years later, Henry Salo found a heap-buffer-overflow in giflib (tagged CVE-2016-3977 2) utility program that converts gif to an RGB file. The approaches these security researchers took to find these bugs is undocumented.

Earlier this year, You et. al. 3, presented a “seedless fuzzer” that uses execution tracing (what lines of code were executed) to develop a map of bytes and their position in the input stream to the effect they have on the program. The authors show that their tool, named SLF, generates 3 seeds and discovers 357 unique program paths in the process of fuzzing giflib. Unfortunately, neither absolute coverage numbers nor the evaluated version of giflib are presented, so we don’t know how their effort compares to ours.

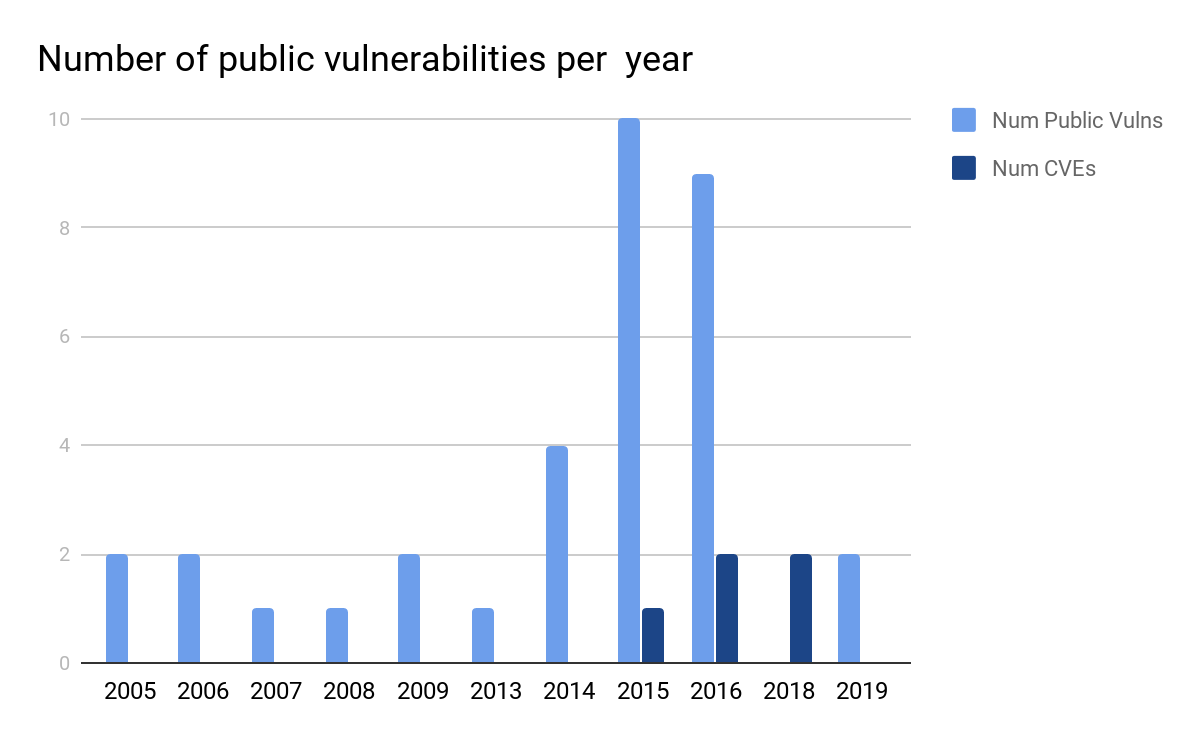

Finally, giflib’s bug tracker itself tracks bugs and vulnerabilities found during its lifetime. The tracker contains about 35 bugs that can be considered security vulnerabilities (crash, information leakage etc.) over its lifetime of a little over 30 years (v1.0 dated 14 June 1989 4). That’s roughly one vulnerability every year, not bad eh?

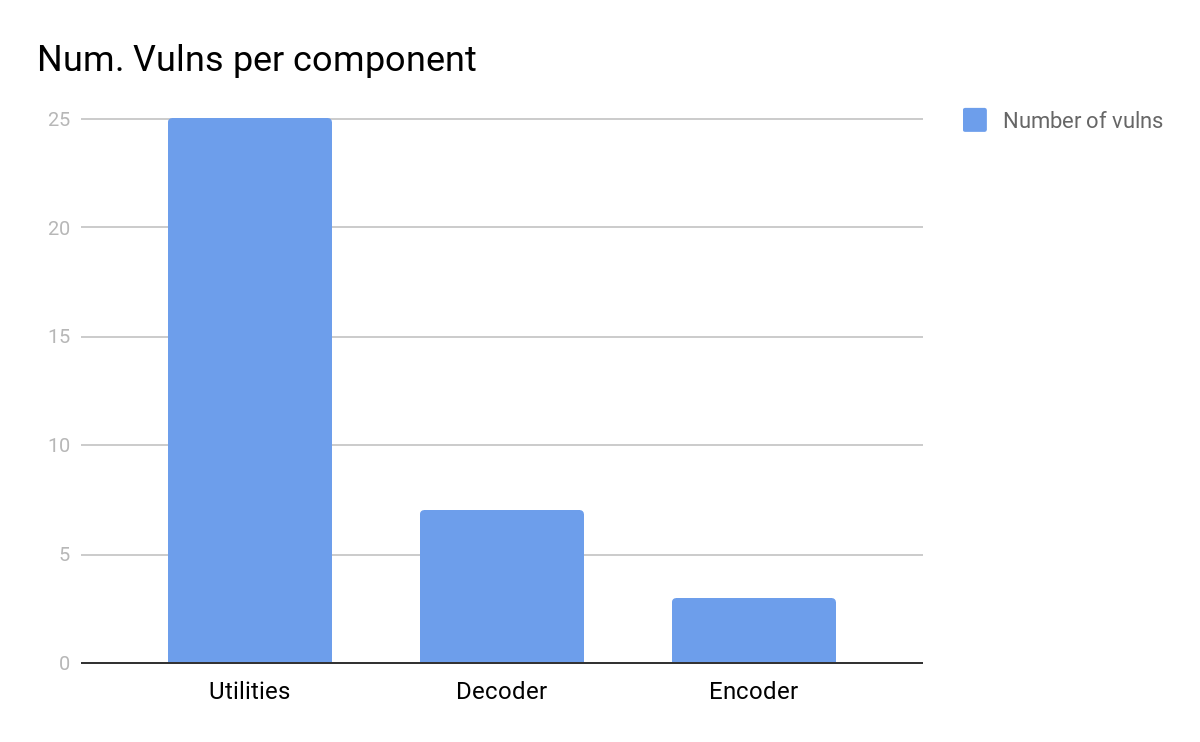

The histograms below shows in which components those vulnerabilities were found and when. Despite the utilities being the most promising target in number of vulnerabilities found,

we decided to focus on the decoder, since it’s the most impactful component.

Giflib background

Giflib is library to parse and extract information from gif files. The code is written in C and since there are multiple intricacies that need to be taken into account when parsing the gif format, we suspect that the library was prone to memory corruption vulnerabilities. Giflib is also one the most popular gif parsing libraries, with over 10k downloads per month on sourceforge 6 and being installed by over 98% of the Arch Linux users 7. Popular libraries like libwebp and imlib2 rely on giflib to do the heavy-lifting when parsing gifs. Because of this prevalence, security vulnerabilities in giflib would put a huge amount of users at risk.

This motivated us to developing a fuzzing setup for giflib and submit it to oss-fuzz, to continuously increase the security of oss-fuzz not only for this release, but all further releases to come.

Fuzzing giflib

We started out with a simple fuzzing harness, fuzzing the dgif_slurp function, which takes raw gif data and parses it into structs that contain, for example, all images stored in the gif file. This already uncovered multiple bugs in the current giflib code, in particular an out-of-memory issue and an integer overflow. However, after that the fuzzer saturated it did not increase in coverage and also did not find any new bugs. In fact, using a good set of seeds and a simple dictionary already allowed us to cover all of the code in dgif_slup.

Looking for ways to further enhance our fuzzer, we 1) extended it to cover more functionality and 2) turned to structure aware fuzzing.

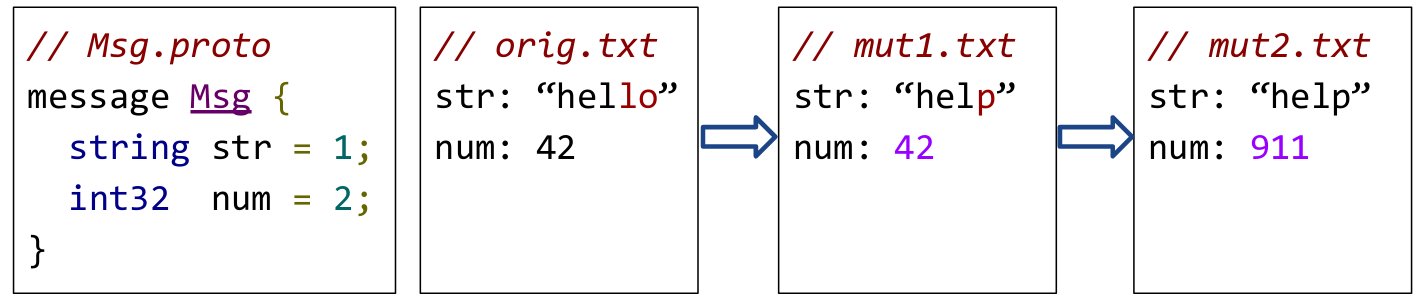

Structure-aware fuzzing enhances libfuzzer to become structure-aware. This means that the researcher defines a protobuf grammar specification of the input format and instead of mutating random bytes in the input, the fuzzer mutates one of the fields defined by the protobuf grammar.

KCC gives a good example of this in 8:

To add protobuf fuzzing to our giflib harness, we had to do two things: Define a protobuf specification for gif files. You can find our current specification here, which is based on 9 and 10. Define a function that converts a giflib protobuf object to a gif file stream. This is relatively straight forward. Our converter is based on a class that recursively calls a function visit, each time with the right data format. You can take a look here. Each visit function adds raw data to the string stream that is then returned as the raw gif data. Our harness then takes the protobuf specification, converts it to gif file stream and passes it to our original gif fuzzing harness:

DEFINE_PROTO_FUZZER(const GifProto &gif_proto)

{

// Instantiate ProtoConverter object

ProtoConverter converter;

std::string gifRawData = converter.gifProtoToString(gif_proto);

if (const char *dump_path = getenv("PROTO_FUZZER_DUMP_PATH"))

{

// With libFuzzer binary run this to generate a GIF from proto:

// PROTO_FUZZER_DUMP_PATH=x.gif ./fuzzer proto-input

std::ofstream of(dump_path);

of.write(gifRawData.data(), gifRawData.size());

}

fuzz_dgif_extended((const uint8_t *)gifRawData.data(), gifRawData.size());

}

Results

After submitting our fuzzing-harness to oss-fuzz, it discovered multiple bugs in giflib which were since fixed. Here is a list of bugs discovered by our fuzzing harness:

Unfortunately, the protobuf fuzzer did not outperform our simple fuzzing harness by any metric. It did not find new bugs in giflib and did not lead to increased coverage in comparison to a fuzzing harness that relied on seeds and libfuzzer’s build on mutations. In fact, it even resulted in less coverage: Since every gif file synthesized by the protobuf fuzzing harness is a valid gif file, our protobuf fuzzing harness now misses some of the error-handling code that our standard fuzzing setup covers.

In the future, we want to tackle this problem by adding a perturbation mechanism to our fuzzing harness, that occasionally allows for a mutation that does not necessarily lead to a valid gif. For example, we could add an optional fuzz-data field to our protobuf specification that, if included, just consists of random bytes (something like optional bytes fuzz_data).

What was still impressive to us is that, aside from error-handling code, our protobuf fuzzing setup reached exactly the same amount of coverage as the standard fuzzing setup, however without requiring any seeds.

The table below compares the two fuzzing harnesses in terms of line coverage.

| Fuzzer type | Percentage (SLoC covered/Total SLoC) |

|---|---|

| Structure Aware | 58.03% (900/1551) |

| Non Structure Aware | 58.99% (915/1551) |

Conclusion

We consider this project a success in two ways: 1) We found three bugs in giflib and the second, maybe more important success is the learning experience we had through our results with protobuf fuzzing giflib.

The bug-finding success is obvious: Despite its security criticality, we were still able to identify bugs in giflib. In that sense, we consider our efforts a success: We fulfilled our goal to make memes a little more secure again - and through our submission through oss-fuzz, our fuzzing harness will continue to do so. However, recent findings in giflib have shown that our current fuzzing setup does not yet cover all of giflib’s functionality, so there is still room for improvement.

The results of our protobuf experiment show just how powerful modern coverage-guided fuzzers such as libfuzzer are when it comes to binary formats. Equipped with good seeds, a well crafted dictionary, and a high execution speed, the coverage guidance is smart enough to cover all of the parsers functionality. If the coverage-guidance is smart enough to continue to outperform our protobuf fuzzer when it comes to bug finding remains to be seen in further versions. Thanks to oss-fuzz, our fuzzers will continue to generate data for our analysis. For now, however, we conclude that the gif format was maybe too simple for protobuf-based fuzzing to show its full power. We think that protobuf fuzzing might reach its full potential when it comes to data formats that even modern coverage guided fuzzers cannot handle because they are too complex: complex compression and decompression formats, compilers and interpreters would be some examples. For those data formats, almost all of the inputs created through mutation would fail to pass even the most basic checks and thus never execute the interesting logic of the program. For those data formats, having a guarantee that every mutation leads to program input that is still valid is really powerful, whereas in the case of gif it does not really give us a performance boost.

Overall, we consider protobuf fuzzing to be a very powerful tool, but it’s definitely not a one-fits-all solution. Especially considering the effort involved when writing a protobuf specification, we advice further researchers to use protobuf when the format is too complex for the standard coverage guided fuzzer to handle.